Massive amounts of footage and logging, no scripts, and quick turnaround: these shows offer distinct challenges

By Ann Fisher

Is reality television an oxymoron? Sure. All media is filtered through people who decide what we should know. Publishers of newspapers, producers of television shows, their jobs are to inform and entertain. What's different with this burgeoning genre of television programming is that the camera doesn't lie and these aren't professional actors. So footage and people are real but everything else is a meticulously crafted attempt to entertain. And it is the manipulation of those images and stories that will define a reality show's success.

Is reality television an oxymoron? Sure. All media is filtered through people who decide what we should know. Publishers of newspapers, producers of television shows, their jobs are to inform and entertain. What's different with this burgeoning genre of television programming is that the camera doesn't lie and these aren't professional actors. So footage and people are real but everything else is a meticulously crafted attempt to entertain. And it is the manipulation of those images and stories that will define a reality show's success.

The challenges are many. Editing reality programs is so unlike editing other genres because the shooting ratio is massive, writing scripts beforehand is impossible and maintaining story arcs is an artform. In a sense, the editors almost become the show's writers because they're crafting a show that was filmed on the fly and often has to be turned around in a millisecond.

With shows like these, supple technical tools are essential. Sony DVCams are small and tape is inexpensive, a must when 190 hours of footage is culled down for use in a one-hour show. The Avid Unity server system seems to be the network of choice for producers who need to offline, online and audio post all at once. In the field, or actually on a Honduran island, an Apple G4 500mhz Titanium Powerbook with external FireWire storage kept one editor working.

There are several tips and techniques on which reality show editors and producers rely. The most obvious may be to digitize much, if not all, of that footage. Reality shows hinge on moments and the right one is worth a thousand words. So, pay attention because all these tips were concocted to overcome the reality shows' special challenges.

Set up an efficient post production system

Nancy Stern, the executive producer on NBC's Lost (three episodes aired in September, the last three began in late December), went to Pow!Pix in Manhattan. President/owner Bob Barzyk set her up a turnkey operation with six Avid Media Composer workstations, a Symphony online station and a Digidesign Pro Tools station all revolving around an Avid Unity server.

"The hardest part about editing a reality show is the amount of material that comes in. I think we had about 300 hours of material for six one-hour episodes that had to be logged and digitized. We had four logging stations at Pow!Pix that went 24 hours a day for about eight weeks," says Stern, who works at Jumbolaya Productions in New York. "I've done a lot of reality but when you're doing other types of shows you basically edit and then you go to an audio facility. Here we were all on the Unity server so that while we were doing sound on a particular show we could also be onlining, and then we could do any fixes on another Avid. We were all sharing the same material, which was so great. We were under a time crunch because our episodes were airing while we were still editing the following week. There's no way we could have done this in an online situation, we had to be in the Avid.

"This is the first time I did it on the Unity. Before that I'd worked on the Transoft. It wet my whistle for being able to go from room to room, and be able to pull up the same material," she adds. "The guy who created this whole thing for me was Bob Barzyk at Pow!Pix. He's a genius when it comes to post and he figured out that this would be the best way to do it. He suggested it and we tried it. I would never edit any other way." The premise of Lost is three teams of contestants are dropped in Mongolia and have to find their way back to the Statue of Liberty. Stern was constantly on the phone with her camera crews and she says about 75 percent of their material was digitized. Six editors worked closely with producers making story decisions. She praises the editors for their patience. "They have to screen all the material. A lot of times when you come back from the field you don't think you can find a single frame that works because it's all been shot so quickly. And the editor makes his or her magic and turns it into something."

Stern is also currently working on a football reality show, ESPN's Sidelines. This one is shot 16-by-9, "just a different button to push on the same equipment," she says. The show is being edited at Wonderland, also in New York, by a Lost editor who copied the Pow!Pix post set-up. Sidelines presents an additional challenge because of an even more rapid turnaround - it airs within days of the footage being shot and players unhappy with what's been caught on tape have been known to cut off access.

"It's not about scripting, it's all about access and people being real and being game to participate," says Stern. "In these reality shows if you're not rolling then it never happened. So you roll on everything. It's better to have it. Tape is cheap compared to a moment."

Decide on your approach

Johannes Weuthen, onset editor for Fox's Temptation Island International Edition; says there are two ways to go: Docudrama or spontaneous. On his first reality job (his background is music videos and feature films), he saw what worked and what didn't with both approaches.

The show was a co-production of Fox, which retained the international rights to the US version and six foreign territories, England, Germany, Benelux (Belgium and Holland), Scandinavia and Portugal. All are airing at different times in the European markets this winter. The show was lensed on Roatan, a Honduran island, this past summer. Each territory shot footage for 12 days for 12 one-hour episodes but not everyone got the material they wanted, so some series' lengths may be revised.

"This was a lesson that certain territory's producers and directors learned - they were under the impression that they would have a lot of control and were going for something like a docudrama. You can only control it to a certain level, and therefore you really have to control the casting. In terms of editing, you have to make it interesting. It's as simple as that. The most important thing about these shows is the cast, that you have the right combination of people. It's like preparing a dish, you really have to get the right ingredients. Some territories had completely miscast," says Weuthen. "Some territories shot everything, which was finally a good decision. The ones that were focusing on doing docudrama, and thought they knew what they needed, were not shooting as much material, which in the end was not the right decision. In a situation like this, shoot what you can get and make sure you do the right logging on location, which is going to be a big deal in post."

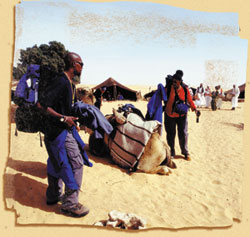

Temptation Island took several couples "at crossroads in their relationships,' put them up alone in swanky resorts, then sent temptors or temptresses to bait them to stray. Cameras capture much of this and, at bonfire events, the mates are confronted with video evidence of their infidelities. Weuthen edited all the bonfire events, working closely with the story editors and directors assigned to each couple. Weuthen's decisions were critical to the shows' most dramatic scenes. The separate territories then took his work and blended it into their shows. Fox provided aerial and beauty shots of the island.

The show was shot with Sony DVCams in PAL format. Weuthen used the Apple Final Cut Pro system, editing on an Apple G4 500mhz Titanium Powerbook with external FireWire storage. "After editing exclusively on Avid systems over the last six years I was surprised how easy the transition was for me and how sophisticated version 2 of Final Cut Pro was," he says.

Weuthen is currently part of the music video production company Giraffe in Los Angeles, which is building up its own post pro department based on the Apple Final Cut Pro system.

Focus on the story

Eli Frankel, lead editor on CBS's The Amazing Race, equates editing reality shows with editing feature films, to an extent. The show's 13 one-hour episodes began airing in September.

"You have shot lists and a script and you try to create the drama through the cuts," he says. "But with reality it's just an entirely different ballgame because not only are you putting together scenes, you're also writing the story as you're putting the show together. One of the problems is there is really no script. I mean the producers come back from the field with a sense of what major beats they want to cover, but that's pretty much the basis from where you start. From there you have to find the story through the material. A lot of times what you find in the way scenes play against each other and the way the stories develop changes from what the perception was out in the field."

In the show, 11 teams of two race around the world, completing tasks along the way. The last couple to reach any of the designated pit stops is eliminated. Each team has a dedicated camera crew. In addition, there are gibs, Steadicams and zone cameras covering the action from all angles. This is the show that shot 190 hours of footage for one-hour episode. Frankel was hired to develop the show's style and story structure, as well as oversee the half dozen editors who worked terrifically for six months.

Unique hurdles for this show included the amount of footage necessary; there were many exotic places that needed to be shown. Relationships between teammates and among the other teams needed to be established. There were incredible action sequences. So many choices. Frankel kept repeating his mantra - watch the narrative flow.

A story department watched every frame of the material, all of which was digitized. Producers noted the main story points. Editors pieced together the main parts of the action, which served as guides for each episode. Tapes were overnighted back to Earthview Productions in Marina Del Rey, Calif. where Frankel and his team worked on an Avid Unity 10.1.1 system with two TB of storage. Six edit bays cranked for six months. Earthview is owned by Bertram van Munster who, along with Jerry Bruckheimer Films, served as executive producer.

"The editor on a reality show isn't just an editor, he's also a writer. That editor has to find the story and literally he's writing it because he's choosing the footage that is going to tell that story," says Frankel. "Develop your sense of story and what builds characters, what makes them strong and how they change. Those skills are as crucial to the editing as actual editing techniques."

On the road again: Pow!Pix takes Unity to Utah

NEW YORK - Bob Barzyk, owner/president of Manhattan's Pow!Pix, knows workflow. He recently took delivery of the largest mobile Avid Unity system in the US and he's taking it to Utah for the Winter Olympics 2002. Pow!Pix is the only outsourced venue there, they'll post figure skating; NBC will use its own equipment for everything else. The post house also was the only outsider at the Sydney Summer Olympics 2000.

Pow!Pix will be there at the specific request of an NBC executive producer. Barzyk does a lot of sports work and he can get huge jobs done quickly. This fall, Pow!Pix rolled into Philadelphia for ESPN's X-Games with its nine-user, three TB Unity, complete with six Avids and three Pro Tools.

"We've been doing shows with six Avids for over three years. We understand workflow. That's all it's about - how to handle massive amounts of data, massive amounts of footage and massive amounts of people quickly, without getting mistakes," says Barzyk. "That's why we invested in barcode readers and all these multiple logging stations. People never used to do that but now that you have so much at stake, and you have to move so quickly, you can't afford downtime. You can't afford a typical mistake like a typo, the wrong reel number. That could slow you down for hours."

Barcodes go on every tape that comes in. Barcode readers are at every logging station. All info is on the network server so editors can instantly pull up exactly what they need at anytime. Everyone working on the Unity system can cross reference and make changes.

In-house, he built an entire turnkey facility to post NBC's Lost reality TV series this fall. The number of DVCam tapes easily topped 5,000. He says with the number of users and the amount of storage needed, he couldn't have done it without the Unity. He thinks he hit the Unity's capacity on that show with six offline Avids, a Symphony online system and Digidesign Pro Tools AV running at the same time; all users were working at a low res 20:1 compression ratio. However, with Pow!Pix's experience with share jobs (the facility still uses Transoft for smaller jobs) Barzyk was confident they could pull it off. The system never crashed.

"We're finally at the point where you can get something done on a very large scale. It's the only way I'd do a reality show. Anything over four Avids we have to go with Unity," he says. What he's done with video, he plans to do with audio - streamline that workflow. - A.F. |