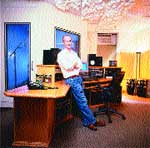

Mike Knoblauch

|

For the character of Spyler - who has a tennis-ball head, eraser body and button feet - Knoblauch used the battery covers on a remote control for the click, click, click of his footfall. He laid a shaker flat and hit it with two blocks of wood to generate both an impact and a shake for the paw sounds of Spyler's small, square dog, CeCe.

Squeak toys gave the right sound for the perambulations of Duck, a rubber ducky with wheels. Toy whistles are heard as Duck spins and shoots out of the frame. The right remote-control car sound for Wheeler, the dump truck, came not from a toy vehicle but a snake toy. Wheeler's voice was derived from vocal vroom-vroom revving sounds, which were pitched up for a childlike effect.

Knoblauch used lots of dominoes in the show for the big-moustached General Domino and his soldiers. "When a character bumps into the marching soldiers and they start to tumble down, I set up a huge run of falling dominoes. It sounds great in the shot."

Knoblauch also tapped library sounds for "boings, dinks and whips. The producers stressed that they wanted things to be silly and goofy so sticking to some sound effects we've all heard was extremely appropriate."

Knoblauch found that Harmony Central's Soundminer, a software program that creates a sound effects database and allows users to search and audition sounds, was a helpful tool. "I'd go into Soundminer, type the sound I was looking for and it would reference the database. It brought up all the appropriate sound effects, I'd audition them, choose the ones I wanted and spot them into Pro Tools. It cut the amount of time I spent searching for sound effects in half."

HBO Family's I Spy: "Even the footsteps of each character are distinctive," says Beatstreet's Mike Knoblauch.

|

Knoblauch also created his own library of voiceover elements - laughs, barking, panting - from which he could pick and choose as needed. "When there was no dialogue and things felt empty, I could pick one of these elements to move the show along."

CREATING A VOICE

Jim McKee and Barney Jones, co-founders of San Francisco's Earwax Productions (www.earwaxproductions.com), are both composers and sound designers with classical music training.

They believe a particular sound design voice is indigenous to each project. "It's up to all involved to see what that voice is, whether it comes naturally or requires lots of patience and observation to discover," says McKee. "The material itself speaks to you about what it should be. You can't force a style or an aesthetic on it."

Their sound design typically combines a number of sources. "Most projects don't have the budget to warrant the creation of a completely new library," McKee reports. "You go in and decide where your efforts will resonate to best effect."

Over the years, McKee and Jones have compiled an extensive sound library. "We came from a theatrical background; San Francisco was a hotbed of experimental stage in the 1980s," McKee says. The material the partners gathered during that time now resides on several large hard drives. IMAX theaters, with 6.1 sound, are another kind of dynamic space for which McKee has created sound design. His IMAX credits include the films Yellowstone and Whales.

Spank's Tim Gedemer: "If you buy into film being an art form, then sound design is a subset of that art."

|

One of McKee's most rewarding projects has been collaborating with The Labyrinth Project and The Getty Research Center on an interactive museum installation drawn from the documentary The Danube Exodus by Peter Forgacs. The sound designer was called in to give "a sense of immersion" to the soundtrack that accompanies a ferry captain's candid footage of the exodus of the first Jews from Hungary in 1939-40. The installation played in a full 5.1 space at LA's Getty Research Center where a touchscreen occupied the central part of the room.

McKee worked on the project for about two years, teaming with the director, programmers and editors. He obtained a large collection of music from composer Tibor Szemzo, including his original score from the documentary and archival clips of music of the era. McKee also found several one-hour recordings of ship sounds made on the actual Danube ferry in 1970. He already had an extensive library of waves and water sounds from Whales.

For the interactive installation, McKee created sound design "that was more abstract than for a traditional feature film," he reports. "The whole room was a more imaginary space where the narrative came from the viewer's imagination. The sounds became part of the environment along with the music."

McKee worked on a Pro Tools TDM system with multiple plug-ins. Miller & Kreisel Speakers donated a full theatrical sound system for the installation so McKee opted to perform the final mix in the space with his Pro Tools. McKee hopes for a continuity of the 5.1 experience when the installation travels to venues in Germany and Holland.

TREASURED SOUNDS

Dane Davis, president of West Hollywood's Danetracks, Inc. (www.danetracks. com), doesn't see himself simply "painting by numbers with sound" in the "see a bird, hear a bird" tradition.

Instead, Davis, who won the 1999 Academy Award for best Sound Effects Editing for The Matrix - on which he was sound designer/supervising sound editor - thinks about "what's happening on screen and what sounds are created in the process of what's happening. You want to find a way to put motivation in the sound, to suggest more is going on than just what you see."

Davis and his Danetracks team had a special challenge in the new Disney animated feature, Treasure Planet, which transplants the Treasure Island tale to outer space where Long John Silver is a cyborg and his pet, Morph, is a shape shifter instead of a shoulder-perching parrot.

"It's set in a future as it might have been imagined 200 years ago," Davis explains. "It's sort of retro-futurism, so we had to find the threshold of the old and the new."

He notes that "Disney-animated soundtracks are usually somewhat simple compared to live-action features such as The Matrix. We create a level of detail that's pretty extreme, so people were worried that our sound might overwhelm the animation." Davis spent two years (with breaks for other commitments) as sound designer/supervising sound editor, working constantly to see how much like a live-action movie the animated feature could sound. In the end, "it surprised a lot of people" that his premise - the animation would be more real and plausible with detailed sound - worked.

The movie's sound effects were recorded at the Danetracks facility using Pro Tools 24-bit systems with multiple plug-ins and stand-alone digital processing programs, including U&I Software's MetaSynth and Sound Hack.

For Long John Silver's mechanical prosthetic arm, which "can do just about anything," Davis says he and sound designer Richard Adrian "tried a million things and picked what worked best [spinning and vibrating friction motors and mechanisms] without conflicting too much with the character dialogue." The sounds were edited and processed to "grow the sound onto the picture" such as a sequence where the pirate's arm whirs and spins furiously as he whips up a meal for the crew.

Supervising sound editor Julia Evershade handled many of the action sounds such as the wooden tall (space)ships' explosions, gunfire and classic-yet-sci-fi swashbuckling, plus the mechanical robot Ben. Andrew Lackey and the rest of the design team devised sound to accompany the gigantic visuals of a black hole and solar storm. "They had to sound expansive, fun and dramatic without blowing the kids out of the theater," says Davis. "We experimented with lots of growling and shrieking sounds for the threat of destruction that had to work with the whistling and howling of the 'etherium' being sucked in and exhaled from the black hole."

He and the directors decided to use his own voice, sped up and pitched higher, for Morph, but he filled his mouth with Jello for gooey vocalizations with no consonants or vowels. Over time Davis developed an amazing repertoire of about 90 emotional categories for Morph with 10 to 40 variations in each.

Davis also squished, splatted and plopped Jello for Morph flying, flipping and melting. To avoid sounding wet and disgusting, he digitally stretched the sounds so they became very springy, "as if Morph's molecules were always rearranging and bumping into each other."

THE CHEMISTRY OF SOUND AND PICTURE

Ultimately, the art of sound design is the result of the chemistry of sound and picture working together to evoke a response.

Executive producers Kelly Fuller and Dawn Rix know a lot about Chemistry. In fact, it's the name of the studio (www.chemistrysound.com) they launched in August to match the artistry of composers and sound designers nationwide with projects seeking top talent.

"Sound design really is an art form," says Fuller. "While most seasoned composers are also well-versed at sound design, our roster includes several veterans exclusively dedicated to sound design. This level of mastery is crucial when a spot is purely sound-driven. In these instances, we will collaborate with four or five top sound designers who will invariably contribute a unique perspective."

For the surreal, multilayered and textured Friend/Hacker spot for Sony PlayStation's Digimon World 3 game from J. Walter Thompson/LA, the partners collaborated with four sound designers on their roster and produced "four completely different approaches," Fuller notes.

"The main idea was that instead of using literal sound effects, they'd take sound design elements and make them part of the music track with different moods and textures," Rix explains. Although clients often decide to combine elements from different sound designers' tracks, for this spot the client selected Miyagi, a sound designer/ composer who distorted and filtered beats and sounds made with MIDI instruments, seamlessly criss-crossing computer and sound design elements for an ominous, frenetic, friend-or-foe atmosphere.

A different take on sound design was required for a quirky Chicago Film Festival promo from DDB/Chicago. Actress Julia Ormond directed the spot, which features a narcoleptic man who falls asleep in his cereal bowl, drops off onto a pizza, snoozes under a lawn sprinkler and dozes while backing out of his driveway. Sound designer Jeff Fuller layered real-life sounds into the spot like splashes, bangs and sprinkler whips and added sounds just offscreen - a radio weather report at the breakfast table, puppy whimpers, a hubcap falling off and rolling down the driveway.

"Where the sound design is placed in the frame makes the entire spot," says Rix. "You crack up laughing when you see it. The guy finally gets tickets for the Chicago Film Festival - the cure for narcolepsy - falls asleep at the counter and slides down the glass with a subtle squeak."

The new company Chemistry is all about "creating interesting and unique tracks," Rix says. "Our sound designers have to be as excited about a job as the agency is. They have to say, 'I'd love to do that!' Then the client is guaranteed to love the tracks they create."